Photo: A view of the Pacific Ocean floor off the coast of Hawaii. Multibeam sonar data. © Territorial Agency

“Water erases all boundaries; and since all the seas of the world converse with all the other seas, the boundaries that history has drawn in the sea are purely conceptual, or derive their geometry from some aspect of the nearest coast,” writes Roberto Casati in his book Oceano. Una navigazione filosofica.

Although the characteristics of seas and oceans, both ecological and socio-political, are constantly changing today, their knowledge is not only partial but is “paralyzed between established forms of cultural segregation and separation between human activities of land and sea” (Ocean Space). The terracentric perspective considers what happens in aquatic spaces as something marginal compared to what happens on land, where our society lives. In order to address the important transformations taking place, it becomes necessary to rethink this relationship between land and sea and to begin to conceive of these aquatic spaces in social terms, as sensitive bodies reacting to “earthly” human activities and thus as spaces of society, rather than spaces used by society.

There are several art projects that want to make a contribution to the debate from the perspective of overcoming the land/sea divide, vividly seeking a break with that separation that disarticulates the discourse in nature/culture. We have collected four projects that, although working on different planes and with different methodologies, are united by the desire to bring – and in some cases ‘bring back’ – maritime practices to the center of contemporary discourse, constantly making a dialogue between what happens ‘on land’ and what happens ‘in the water’: rethinking this relationship and abandoning the assumption that the existence of society exists only where human beings physically live, is only possible if we first imagine a life in which the Ocean is intrinsic.

Dineo Seshee Bopape, Ocean! What if no change is your desperate mission

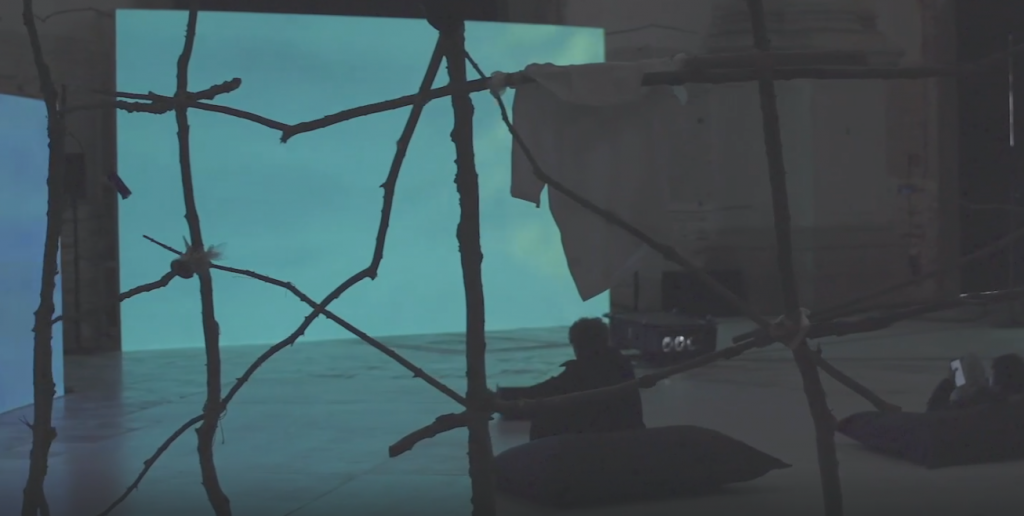

View of the exhibition The Soul Expanding Ocean #3: Dineo Seshee Bopape, Ocean Space, Venice, 2022. Commissioned and produced by TBA21-Academy. © Matteo De Fina

As part of The Soul Expanding Ocean exhibition curated by Chus Martínez at Ocean Space (Venice), South African artist Dineo Seshee Bopape is exhibiting lerato laka le a phela le a phela le a phela / my love is alive, is alive, is alive. The work, commissioned by TBA21-Academy, is the result of a trip to the Solomon Islands, from where the artist makes her way to the plantations of the Mississippi River to Jamaica, then back home to South Africa. From this journey comes a project that traces the history of the transatlantic slave trade and looks to the Ocean as a repository of colonial stories. Stories that are told by microorganisms, by rocks and seaweed, by waves and the voices that move with them. It is a work that teaches us to understand that “ancient and legendary times do not belong to the past, because the colonial era of oppression is not past history, just as destruction and exploitation of resources are not,” writes curator Chus Martínez.

The Soul Expanding Ocean is one more step toward uniting the land and the memory of the oceans: they contain part of human history and as such, just as the work itself invites us to do, they should be listened to.

Carlos Casas, ARAL. Fishing in an Invisible Sea

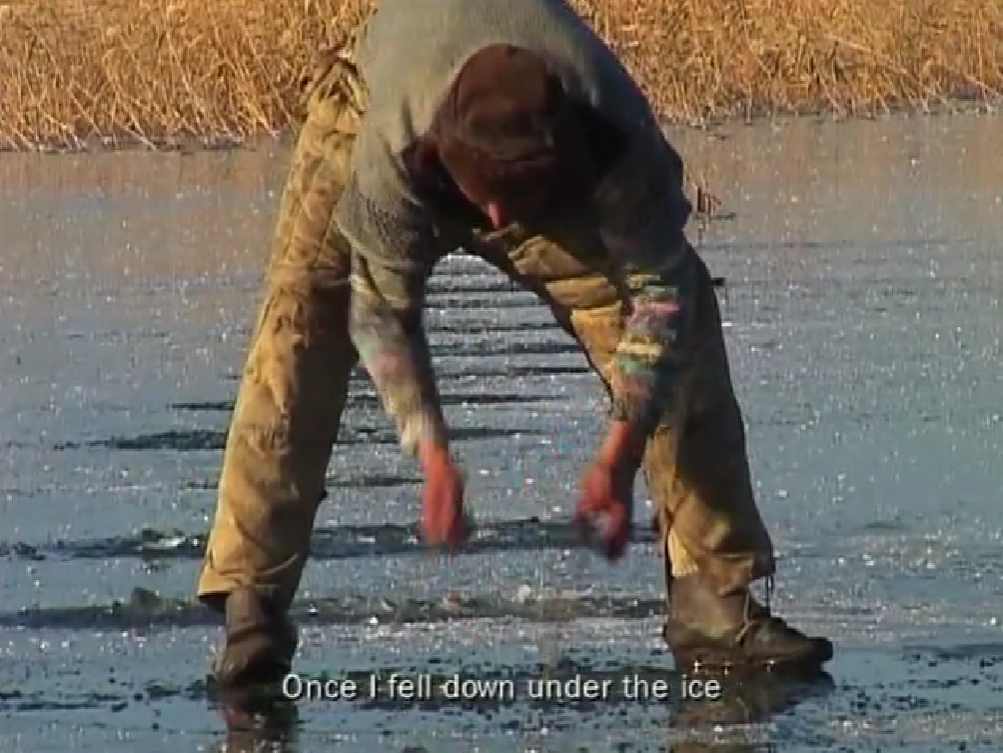

Carlos Casas, ARAL. FISHING IN AN INVISIBLE SEA, Moynak. Uzbekistan. 2004, DVCAM Color, 52 min

Carlos Casas made a documentary film in 2004 set in Uzbekistan, more specifically around Aral, in Monyak, that explores the lives of three generations of fishermen-the last remaining ones. It is a journey inside their everyday life of waiting and struggling to survive in one of the places most affected by environmental disaster. The Aral Sea, now one of the most remote places on the planet, was originally one of the largest lakes in the world: its waters divided the Soviet socialist republics and the present-day states of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. In the 1980s, its waters were widely exploited to feed cotton monoculture, an abuse that caused a vast reduction in its size until it (almost) disappeared.

Casas says he wanted to portray “the process of the death of a sea through the last three affected generations, from the old, retired fisherman who lived the sea, to the adult generation that still survives through fishing in the remaining lakes, to the desert generation that survives from nothing, trying to maintain traditions and the hope of a more hopeful future return.”

Barena Bianca collective and Ilaria Genovesio, Never let me Gò, Tunaight

From the video of Never let me Go, Tunaight, Barena Bianca

The Barena Bianca collective, formed by Fabio Cavallari and Pietro Consolandi in the summer of 2018, was born in the Venetian lagoon with the aim of bringing to light many of its ecological and sociological issues, adopting the Barena, a typical Venetian salt marsh essential to the city’s survival, as its emblem.

The project Never let me Gò, Tunaight, in collaboration with Ilaria Genovesio, creates continuity between the cities of Istanbul and Venice, through the identification of one or more extinct and alien marine species that share the Sea of Marmara and the marine area of the northern Adriatic Sea and the Venetian Lagoon. Research that brought to light pressing issues – and shared in the two cities – such as pollution, globalization, climate change, overfishing, food, tourism and biodiversity.

“During our time at PASAJ, we made mobile, flying sculptures depicting a goby (gò in Venetian), a tuna and sea nuts – an invasive species, a ctenophore that thrives in warm waters harming local marine life. Two iconic fish, the Gò for Venice and the Tuna for Istanbul, found in both waters and sharing glorious pasts and a somewhat critical and precarious present. In contrast, the sea nuts are the image of a contaminated present, at odds with the fragile balance of the seas, and encroaching in harmful ways on fragile ecosystems such as the Venice Lagoon and the Bosphorus.”

Salvatore Iaconesi and Oriana Persico, U-DATInos. Sensibili all’acqua

The Mare Memoria Viva Ecomuseum is a community space, created together with the inhabitants of the seaside boroughs, which hosts a choral narrative and has initiated a journey of rediscovery and reappropriation of the relationship between the inhabitants of Palermo and their sea. Does the sea in Palermo still exist? In recent decades, the relationship between the city of Palermo and its sea has become controversial. The sea that washes the Sicilian capital has been intensely exploited, and this has brought ruins and degradation to the coast. Giving Palermo back its sea is therefore the mission of the Ecomuseum.

This healing work, last year, went as far as the Oreto River where an artwork dedicated to the river itself was created. The work in question is called U-DATInos. Sensibili all’acqua and was conceived by artist duo Salvatore Iaconesi and Oriana Persico. It is a A meditative space to listen to Palermo’s water and question the future of the Oreto River. A platform of expression and activation for the city’s inhabitants and communities. “At the mouth of this river, immersing ourselves in this complex territory, we will try to experiment with new rituals that connect us to the waters of Palermo: to become sensitive to the environment and imagine new alliances between human and non-human actors, art and science, innovation and society,” the artists write.