Philosopher and farmer Luca Cinquemani in conversation with researcher and director Habib El Ayeb

L. C.

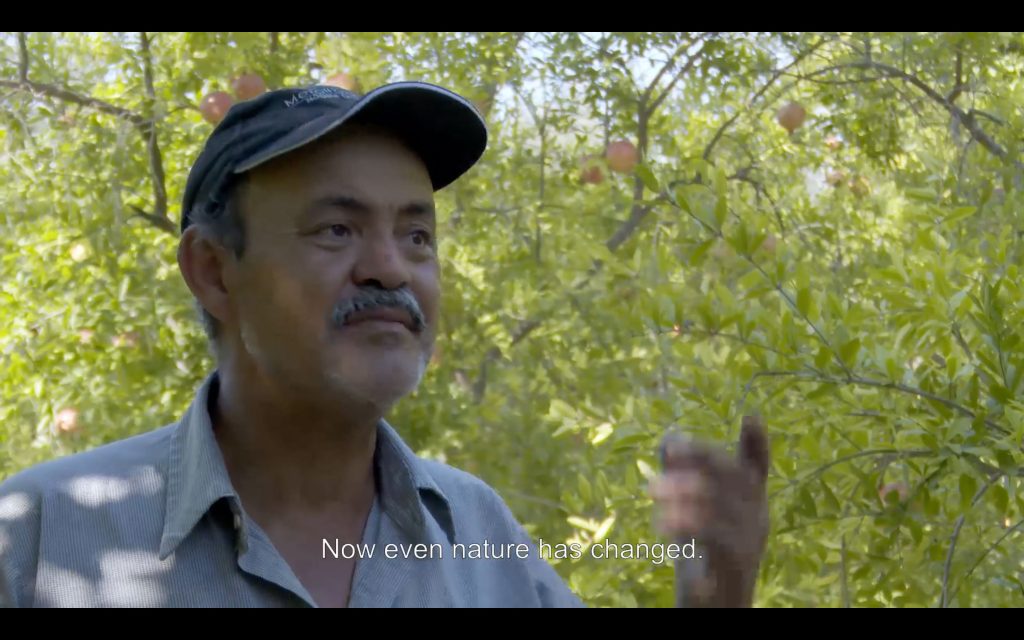

Your film Om Layoun reveals the terrible reality concerning water resources in Tunisia. Capitalistic companies consuming big amounts of water, chemical producers for exemple, the cultivation of agricultural products for export that require a lot of watering and overall bad institutional policies are some of the problems that led up to the current critical water situation in Tunisia. In the last couple of months me, Fabio Aranzulla with whom I founded the agricultural association Aterraterra, and Enrico Milazzo, researcher and part of Collettivo Epidemia, have been analysing the effects of global warming on water scarcity here in Sicily and the Mediterranean area. One big topic was the importance of „going back“ or „rediscovering“ the use of native varieties of food plants – in particular cereals, but also vegetables and fruits – already adapted to specific habitats, including arid ones. Another topic that we focused on was the (re-)introduction of spontaneous food plants – adapted to only needing rain water – which have been gradually erased, forgotten or marginalised in local eating habits.

H. A.

You mentioned two crucial issues, the problem of water and the problem of food sovereignty. My starting point is: there is no water scarcity, at all, nowhere. The question should not be about scarcity but how do we use the water we have? If you use water to feed the local population, in Tunisia there is enough water for everybody. It is not a problem of demography. We could survive with the water we have under the condition that we use water and land only to produce food. The problem is that a big amount of land and water are used not to produce food for the population but for export! This is the problem of policies which are based on the principle of food security, not food sovereignty, as food security is based on the principle of comparative advantage.

The second point you mentioned is another important topic. “Local” means, first of all, to stop importing seeds, whatever they are, and reproducing seeds locally. We need local produce, but this requires an orientation of policy towards producing food instead of producing food for export. The only possibility to produce enough food is using native seeds. If you use local native seeds, you automatically strengthen the local ecology and local environments. By doing so we can reach a balance between using and protecting natural resources.

L. C.

Capitalistic policies put this balance at risk. Not only in Tunisia, but everywhere big companies developed varieties that aren’t able to reproduce through their seeds, which leads to the farmer being dependent on the company, having to re-buy their plants/seeds season after season. This leads to a marginalisation of native seeds and to a reduction of biodiversity, loss of food sovereignty and destruction of local ecologies. How is the situation of the use of local seeds in Tunisia and which are the institutional policies on this topic? What are the organisations doing to help their diffusion?

H. A.

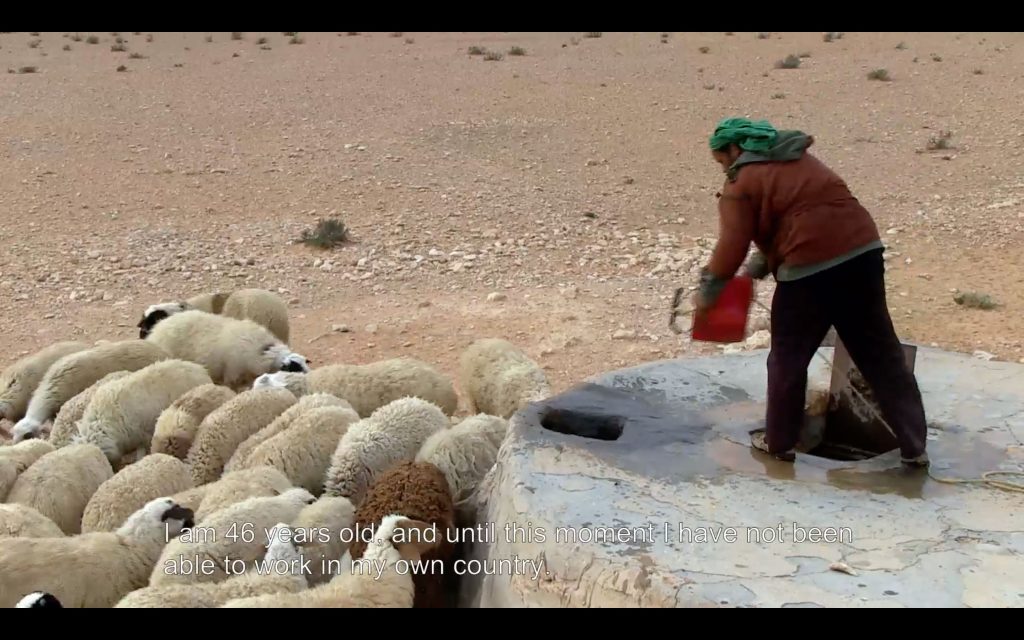

Still in our country and in many other countries of the global south there are thousands of small farmers who use only local seeds. The problem is that they cannot compete with the agribusiness market. Probably 60 % of the small farmers in Tunisia are poor and have to switch to other activities, like the production for the international market, as a strategy to survive and secure a minimum income for their food and other daily life needs. So, a very important point is to protect the small farmers. Our organisation OSAE and other organisations are working on this specific point: how to advocate for small farmers’ rights, the rights of water, seeds and local food security. And then there is the state with its different institutions and organisations. The problem lies there because the same policy, which has been formally initiated at the beginning of the colonial period, is still in effect. Ten years after the revolution, people and the state still push for more export and they don’t consider importing food to be a problem because the practical risk of getting Tunisia under embargo seems a bit far from reality.

A state institution that is doing serious and interesting work is the genetic bank National Genetic Bank (BNG). The problem is that state policies are working with local seeds as “museum objects” for conservation. The goal of these policies is not to strengthen the food security of small farmers but to build a new museum, a process of “museification” of the local varieties. The production and the reuse of local varieties is not being pushed enough because there are no policies that aim to do so. An important step would be to connect the work of the genetic bank with food policies oriented towards the cultivation of local varieties.

L. C.

The point is to move from policies oriented towards an agriculture that uses imported seeds and produces products suitable for the international market to policies that focus on securing food sovereignty of the local population, for example by using native seeds?

H. A.

We should decide to stop importing seeds and agricultural products from abroad. The problem is how to fix the policies and the need for a clear strategy. One of the most important strategies would be to stop greening the desert for cultivation and to stop exporting agriculture products, especially the ones coming from artificially irrigated lands.

L. C.

How much of the colonial period is still alive in contemporary Tunisia and what is the impact of this difficult heritage on agricultural policies and the management of natural resources?

H. A.

Colonialism never ended, today it is the same as it used to be. Nothing changed. At least, during the colonial period – this is a paradox – the French state cared for their food sovereignty. They used to put a lot of money into agriculture here to produce what they needed in France. Now we are continuing with the same colonial policies but without the money they used to invest.